Articles

I am sometimes asked about articles I've published (but not that often!). I thought it would be handy to post them here.

All articles are copyright and may NOT be reproduced elsewhere without EXPRESS PERMISSION.

- Lindsey Davis: An Interview with the Author of Silver Pigs.

- Fluent Latin

- A Ghost's Tale: Musings on the Film Scenario

- Just Charming: Tapping into the Latin Magic of Harry Potter

- Audiocassettes, Anyone?

- Twice a First Year Teacher

- Leafing Out: State Vice Presidents, the CPL and You

- Validating Spanish in the Latin Classroom

- Review: Tonight They All Dance

- Review: Arbor Alma: The Giving Tree in Latin

- Review: What Will I Eat? Quid Edam?

- Getting on Target: An Analysis of a Middle School Classroom

- Grammar and CLC: Keeping it in Context

- National Latin Teacher Recruitment Week: A Look Back

- CarPe Latinam: CPL's Tips for the Latin Classroom

- CarPe Latinam II

- CarPe Latinam III

- Survey Results from the 2nd Annual National Latin Teacher Recruitment Week

Fluent Latin

The Cambridge Latin Course, from its inception, boasts that it produces true readers of Latin. Unfortunately, most of us here were taught Latin "the old-fashioned way", with lots of grammar, declining, conjugating, translating into written English, and very little training in how actually to read Latin fluently. In college, I was a diligent student. I prepared for class for hours just so I would seem halfway intelligent. But I had a horrible suspicion that I would never make it in grad school. Why? Because I could not read Latin fluently--or even semifluently. Nevertheless, I went on to teach high school using the old Ben Hur Jenney text, happily declining and conjugating and writing out tons of translations in something resembling English.

In the fall of 1992 I became the editor of the Texas Classical Association. I had left classics a few years before, disenchanted with my first year in the classroom and feeling that there was something wrong in the way I had been teaching Latin. Now it was time to find my way back to classics through being an editor and to try to give at least something back to all my teachers and professors, even if it was only through producing publications for the association.

In the summer of 1993 I read "Decoding or Sight-Reading? Problems with Understanding Latin" by B. Dexter Hoyos of Sydney, Australia in Classical Outlook. It was what I had been looking for for years--an explanation to what I was doing wrong. I was a first-class decoder. My eye was trained to find the subject and then the verb at the speed of light, zipping down past all the tangled clauses and phrases in between. What I couldn't do was start with the first word in the sentence and take each word as it came. I never knew you were supposed to with Latin anyway.

The article, plus my correspondence with Dexter Hoyos, led to the creation of the manual, Latin: How to Read it Fluently. I have had a copy for a couple of years, but it wasn't until fall of 1998 that it actually was published by the Classical Association of New England and made available to others.

So, I confess upfront that virtually nothing in this talk is an original thought of my own. It comes directly from Latin: How to Read It Fluently, which is available from the CANE for only $5, and I have 20 copies here that I've been given permission to sell for CANE which you can purchase from me during a break.

Hoyos' manual provides some basic, logical rules for truly reading Latin--rules that can be practised and put to good use, thereby opening the possibility for reading not just a handful of lines of Latin at a go, but pages if not whole books, like others do studying modern languages. Let us now go straight to the rules, which you have on the handout. I'll also put them up on the overhead. And let me add Hoyos explains each rule with a kind of clarity I cannot possibly do justice to without resorting to reading his manual outloud, which I will refrain from doing until the end.

Rules for Reading Latin (Prose)

Rule 1 A new sentence or passage should be read through completely, several times if necessary, so as to see all its words in context.

Rule 2 As you read, register mentally the ending of every word so as to recognise how the words in the sentence relate to one another.

When we are teaching our students to read, especially early on in a reading text such as the Cambridge Latin Course, it is vitally important to stress learning the endings. Criticism of these texts often consists of the storyline being so easy to follow that learning the endings often seems unnecessary to students. But lexical meaning is only half of a Latin word--the easy half to register. Thus extra time and practise will be needed to train the brain to register endings.

Reading a sentence all the way through completely will also require practise and diligence, especially with a long periodic sentence for which several readings may well be an absolute necessity.

Rule 3 Recognise the way in which the sentence is structured (its Main Clause(s), subordinate clauses and phrases). Read them in sequence to achieve this recognition and re-read the sentence as often as necessary, without translating it.

It is critical to recognise the structure IN SEQUENCE. So often the main clause has little meat to it, as we shall see in a moment, and the true action is held in the series of clauses and phrases. And here is something that may be difficult for a lot of students (I know it was for me): reading without translating.

Rule 4 Now look up unfamiliar words in the dictionary; and once you know what all the words can mean, re-read the Latin to improve your grasp of the context and so clarify what the words in this sentence do mean.

Rule 5 If translating, translate only when you have seen exactly how the sentence works and what it means. SUB-RULE Do not translate in order to find out what the sentence means. Understand first, then translate.

Understand first, then translate. We are not stuck thinking like decoders anymore. By following the rules that we have so far, it is much easier to see that Latin is not a word for word code. Once we truly understand the sentence or paragraph, then we can more easily write an intelligent translation, or better yet, our students can write an intelligent translation free from awkward phrasing from time-consuming decoding.

These first five rules are the basic rules and can easily be taught from day one in a Latin class.

Rule 6 a. Once a subordinate clause or phrase is begun, it must be completed syntactically before the rest of the sentence can proceed.

b. When one subordinate construction embraces another, the embraced one must be completed before the embracing one can proceed.

c. A Main Clause must be completed before another Main Clause can start.Rule 7 Normally the words most emphasised by the author are placed at the beginning and end, and all the words in between contribute to the overall sense, including those forming an embraced or dependent word-group. A word-group can be shown by linking its first and last words by an "arch" line.

Rule 8 The words within two or more word-groups are never mixed up together: "arches" do not cut across one another. But an "arch" structure can contain one or more interior "arches"; that is, embraced word-groups.

(We'll look at these arches in a moment.)

Rule 9 All the actions in a sentence are narrated in the order in which they occurred.

Rule 10 Analytical sentences are written with phrases and clauses in the order that is most logical to the author. The sequence of thought is signposted by the placing of word-groups and key words.

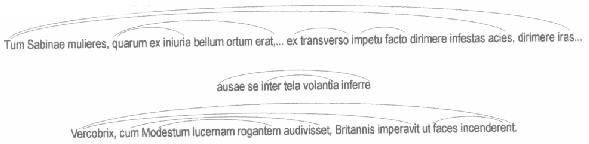

Let's look at a few arch diagrams. Although they are difficult at best to use with a typical lengthy Latin sentence, unless you have a very wide sheet of paper, a shorter or truncated sentence or even just a phrase can demonstrate this concept clearly.

(my apologies for the poor scan below)

More useful, perhaps, is what Hoyos calls a Line Analysis in which you can easily demonstrate word groups and sentence structure without taking the Latin out of its order. This Line Analysis is simple to do and is an extremely useful tool that you can have your students do.

Here's the passage under discussion, which you will also find on your handout:

Tum Sabinae mulieres, quarum ex iniuria bellum ortum erat, crinibus passis scissaque veste, victo malis muliebri pavore, ausae se inter tela volantia inferre, ex transverso impetu facto dirimere infestas acies, dirimere iras, hinc patres, hinc viros orantes ne se sanguine nefando soceri generique respergerent, ne parricidio macularent partus suos, nepotum illi, hi liberum progeniem.--Livy Ab Urbe Condita 1.13.1-2

I think it is well worth quoting directly from the manual here:

"[This passage] opens with the subject of the Main clause: Tum Sabinae mulieres, ... (and note the comma--punctuation again). From just these three starting words the reader rightly expects that:

- the Main Clause's verb(s) will be plural

- the Main Clause will be along the lines of Tum Sabinae mulieres + plural verb(s) + object or objects if a verb is transitive;

- but the verb(s) will not be arriving right away (remember the comma);

- and the intervening word-groups will add background and detail to whatever the Sabinae mulieres are finally going to do.

The same logical principle of LOGICAL EXPECTATION guides you through the rest of the sentence. Its format can be analysed by putting each word-group on a new line:

| 1A | TUM SABINAE MULIERES, | start of the Main Clause |

| 2 | QUARUM {EX INIURIA} BELLUM ORTUM ERAT, | relative clause (->mulieres) embracing prepositional phrase |

| 3, 4 | CRINIBUS PASSIS/SCISSAQUE VESTE, | two ablative absolute phrases |

| 5 | VICTO MALIS MULIEBRI PAVORE, | third abl. absolute phrase |

| 6 | AUSAE SE {INTER TELA VOLANTIA} INFERRE, | participial phrase (->mulieres) embracing a prepositional phrase (inter+acc) |

| 7 | EX TRANSVERSO | prepositional phrase (directional) |

| 8 | IMPETU FACTO | abl. abs. phrase |

| 1B | DIRIMERE INFESTAS ACIES | completion of Main Clause |

| 1C | DIRIMERE IRAS, | co-ordinated second Main Clause |

| 9 | HINC PATRES, HINC VIROS ORANTES | participial phrase (-> mulieres) |

| 10A | NE SE | start of negative indirect command |

| 11 | SANQUINE NEFANDO | abl phrase of means |

| 10B | SOCERI GENERIQUE RESPERGERENT, | completion of 10 A |

| 12 | NE PARRICIDIO MACULARENT PARTUS SUOS, | co-ordinated second negative indirect command |

| 13 | NEPOTEM ILLI, HI LIBERUM PROGENIEM. | noun-phrases: illi and hi in apposition to subject implicit in macularent |

This can be termed a "line-analysis", about which more below. It is important to note that this layout does not affect the word-order. It shows, though, how each word-group contributes a particular detail--an action, a description or a psychological feature--to the developing sense of the sentence.

Another very important point: each word-group is placed where it is most relevant.

- the abl absolutes forming groups 3, 4 and 5 are placed to describe the Sabinae mulieres as these burst on the scene. The relative clause (group 2) by contrast refers to a past event (their iniuria) and so precedes 3, 4, and 5.

- The Main Clause verbs (in 1b/1c) have to come after the participial phrase (6 ausae etc.) because such was the sequence of action.

- For the same reason the women's pleas (groups 9-13) follow the Main Clause's actions--they had to interrupt the combat first, then plead with the combatants, and the narration matches this.

- Word-group 13, in apposition to 12's implicit subject and its object, follows 12 to close the sentence with a vividly antithetical figure.

Thus the format of [this passage], which to a new reader's first glance might look like an indigestible tangle of verbiage, turns out to be commandingly rational. Just as important, the reader can learn to follow and understand this format while reading it--eventually, even when reading it for the first time."

And that's where I'll end quoting from the manual.

The Cambridge Latin Course is a wonderful text for training students to read Latin. But the text can't and doesn't do it all. As teachers we need to be aware of what constitutes good reading skills and how to avoid the pitfalls of decoding. The best thing about these rules is that they can be taught from day one. They should be posted on the walls in all secondary classrooms or even printed on bookmarkers to keep in Latin texts, to remind the student that they are learning to read a rich, vibrant language, not decode a secret message.

* * *

(this version of Fluent Latin was presented to the NACCP, Summer 1999 and differs slightly from that which was published in the Ecce Romani Newsletter.)

Latin: How to Read it Fluently by B. Dexter Hoyos can be purchased through CANE's Instructional Materials.

July 30 , 2001